A Collection of Stories and Poetry

By Members of the Echenberg Family

On the Occasion of the 4th Echenberg Family Reunion

August 25th-27th, 2006, Orford, Quebec

Contributors: Ruth Tannenbaum, Myer Kitner, Deborah Sheppard, Ann Echenberg, Leon Echenberg, Hope Finestone, Peter Tannenbaum, Sharon Weinstein, Jackie Friedman, Murray Richman

©Echenberg Family Reunion Committee, 2006

Ostropolye Then

The Kitners of Ostropolye

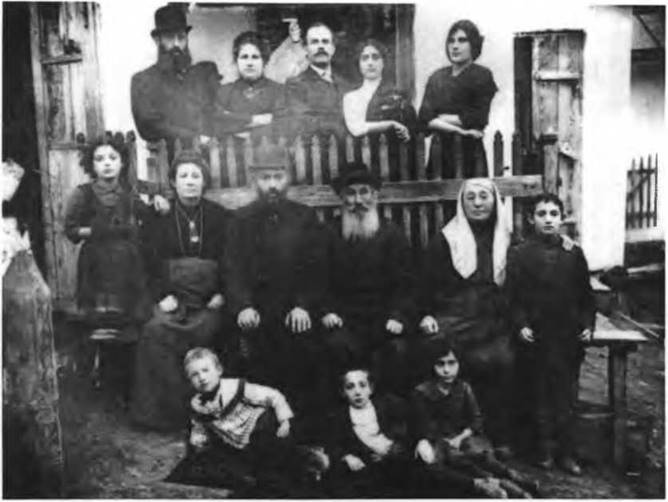

Family picture, Ostropolye, circa 1910

The Gems We String Together

Tsitsinye

Leon’s Winter Boots

Ready for Passover.

Ostropolye Now.

One Way Ticket.

A Difficult Beginning and Easier Endings.

Grandfather’s Table.

Visiting Relatives.

Lighting the Gas.

The Weinstein Family

Family Picture, Sherbrooke circa 1910.

Iches

The IODE in My Life.

Recipe Box.

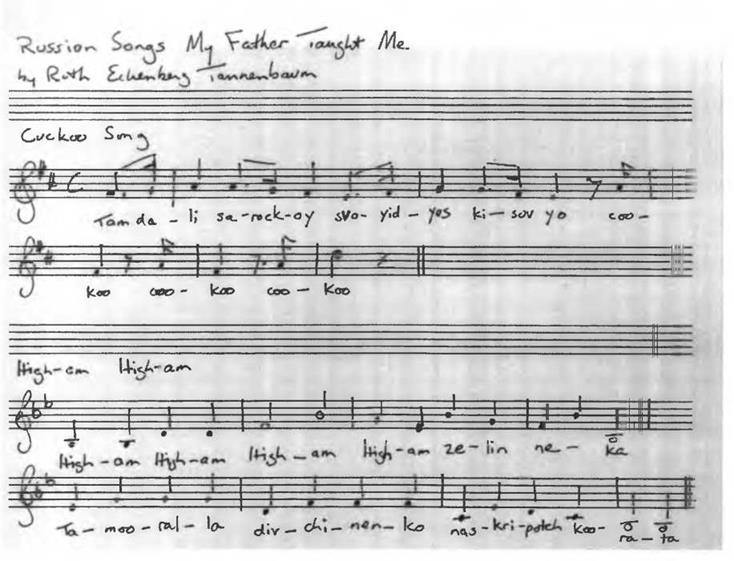

Russian Songs My Father Taught Me.

Anne Caplan.

Uncle Sam.

The Hills of Home.

Eastern Townships.

Dr. Tannenbaum, I presume.

Nuclear Medicine.

La Boulangerie Saint Laurent.

Letter from Murray Richman.

My Mother’s Cousins.

Jessica’s Bat Mitzvah.

Dear Cousin:

Welcome to the fourth Echenberg family reunion. It is now twenty years since the first one we celebrated in 1986, the centenary of the arrival of the first Echenberg ancestor, Moses Echenberg, in North America. It is an amazing accomplishment that we still manage to get together on masse every six years or so to renew our ties and connections, and reaffirm the specialness of being “an Echenberg”.

Every family has its history, but I don’t know of any other that has chronicled it so completely and thoughtfully as have we: a collection of photographs and other memorabilia, maintained to date by our archivist Hope Finestone, our massive and complex family tree that continues to grow and flourish with an ever more splendid variety. And now we add this addition: a book of poetry and short stories about Echenbergs by Echenbergs.

In undertaking this project, we were very fortunate to already have a store of wonderful stories and anecdotes recorded in writing or taped by relatives who sadly are no longer with us, but have left us a precious legacy of their memories. The story by Myer Kitner is actually an excerpt of his autobiography. My mother made a point of putting to words many of her childhood memories dating back to the twenties. Most of her stories are found here. As well, we have received submissions from a number of you, all of which have been included here. I hope you enjoy them.

This collection of stories and poetry is only the tip of the iceberg. There are many more stories out there, waiting to be told and heard. It is my sincere hope that we can continue to add to this modest opus, so that it remains a perpetual work-in-progress as we live out our lives and remember those who are dear to us. If it is the collective will of the family, I will happily continue to receive stories from any of you, and add them to what we already have.

Reading these wonderful stories, remembering the people who figure prominently in them (and those who told them), I am filled with a sense of belonging, and with pride of who we are and what we have accomplished. Not only do they describe where we have come from, but they also give a sense of what we have become. Our family has evolved over the decades. But in the end, we remain close because we love one another, and that is the best definition of what being a family means.

With love,

Peter Tannenbaum

Ostropolye Then

By Ruth Echenberg Tannenbaum

My family history is bound up in a commonality, rooted in the shtetl of Ostropolye, situated in the Pale of Settlement, a territory variously ruled by the Poles and Russians. I rely on oral history; there are no written documents. My cousin Dean Echenberg recently went to Ostropolye while on a visit to the Ukraine. He brought back pictures which captured some of the features of the town and countryside. They gave a physical reality to the stories I had heretofore experienced as childhood memories of my father and uncle.

Ostropolye was situated on the Slucz River, and had a population of about 10,000 people. It was a market town, and thus it had strong ties with the surrounding countryside. The farmers and peasants made up the clientele of the town’s wares. The residents consisted mostly of merchants: millers, watchmakers, shop keepers, and so on. The Jewish community was pretty self-sufficient. It had within its confines the human and material resources needed to be fairly independent. I don’t know if there were any “professionals” — doctors, lawyers and so forth — living in Ostropolye. There probably were not; it was likely the villagers had to travel elsewhere to seek out those kinds of services. For education the town had the cheder or Jewish school and the Russian Gymnasium to prepare students for the professional schools.

The big towns in the region were Berdichev and Zhitomir. My paternal grandmother, Hanna Shochet, came from another shtetl. Her father was a rabbi, probably a schohet. His family was reputed to have descended from the Bal Shem Tov, the founder of Hassidism. Great emphasis was put in my father’s family on Balibatischkeit, on being refined or finer Menschen. There were all kinds of social rankings in the Jewish community. My father’s father married a woman who had class. She met the criteria for the son of Baba Rachel and Fette Alter. My great grandfather was named “Alter” or eldest in order to fool the devil. It was a way of protecting the newborn child, according to some superstition.

Baba Rachel, like her daughter-in-law, had also come from another shtetl. She brought enormous prestige to the family, since she was more highly educated than most of the women of her generation, especially in bookkeeping. Her father had been a wealthy merchant in a neighbouring town. He may not have had sons, so he taught the art of double entry book keeping to his daughter. This was a source of great Iches, or family pride.

Counting

Ras dva driche tereya piat

Pistev zychick pogolyat

Folk Saying

Borsht a kasha pishta nyasha.

(Borsht and kasha is our food).

The Kitners of Ostropolye

By Myer Kitner

Meyer Kitner was firmly standing on the clay cliff in Ostropolye1. The year was approximately 1906, at the turn of the 19th century. He looked toward the great ball of fire on the eastern horizon that slowly emerged as the rising sun. The sky was brightening, illuminating the horizon with a line of gold as the sun was crept up, higher and higher, turning the rainbow colours into a beautiful view.

The different shapes of the clouds were framed in gold and as the sun kept rising they kept changing in shapes and colours, beautiful purplish hues, red, orange, and changing the different shades of blue in the clouds. He could never stop marvelling at the beautiful sun gradually lighting up the sky. He turned his back to the sun to see the effects it was having on his little town of Ostropolye. Like magic, as the sun was throwing more light into the shtetele. It was waking up.

Doors were starting to open to welcome in the warmth and comfort of the sun. People were awakening, starting into their regular routines. Now and then, you would see someone throwing a pail of dirty water out onto the grass. One after another chimneys poured streams of rising smoke, curtains were withdrawn and windows opened to greet the warm sun.

That western part of Ostropolye had three of four rows of homes on parallel streets, all running from east to west. All the streets had wooden lateral sidewalks and most homes had wooden fences. Some had wooden frames and others were made of clay. They were all more or less in a straight line. The first street was a row of small shops all facing a very big stretch of land which was used for a market. All of these shops had clay floors and were kept warm with hot coals in pails. You also had to dress warmly to sell your wares in these shops when it was cold.

Meyer Kitner felt good this morning. He was a man of God and very grateful that his living him provided him with a comfortable way of life, and most important of all gave him lots of free time to be home and study the Talmud.

Russia during the reign of Tsar Nicholas II contained many large tracts of land, owned by members of the aristocracy, or Pritzen as they were called. Very often they bought and sold property between them, sometimes many, many square miles in area. When a parcel of land like this was put up for sale, the prospective buyer would hire Meyer Kitner to evaluate the land. He would walk the area, examine the ground, judge the quantity of lumber, and note the quantity of the water in the streams and their contents.

Because of his impeccable reputation as an honest, fair and capable man, he was amply paid and could choose the jobs that best suited him. He worked when it was convenient for him, avoiding jobs around the Jewish holidays.

When he was not working he spent his time in Ostropolye, where, widely respected in the shtetl, he acted as a judge to settle estates, arguments, and was very active in the welfare of the Jewish community.

No wonder he felt good today. He was looking at a small piece of land on which he would build a home for his loving wife Maita Libbe, and his precious sons, Neevtou (Nathan) and Shama (Charles). He had seen it the day before and had come back to examine it in the bright sun, and conclude the purchase. He was standing on a clay cliff. Before him a narrow road wound down a small hill and curved almost at right angles onto a bridge. About four hundred yards behind him, the river broke into a waterfall just under the bridge, pouring a thin stream of water that pounded the rocks below in a steady, powerful flow, creating a welcome sound that felt like a heartbeat, a sound that he associated so strongly with the village that if it stopped it would lose its identity. The river was starting to sparkle with the reflections of the sun.

On the other side was the eastern part of Ostropolye, called Kalenev. The poorer people lived there in rows of shacks, including the infamous horse thieves of Ostropolye, who could steal a horse and change its colour, so that when the owner would see it the following week he would not be able to recognize it or identify it as his own.

The river some two hundred yards behind him was glistening with the sun’s rays, which cast a long shadow from Meyer’s body onto the piece of land that lay directly across the road running downhill to the bridge at the east end of the large market place. It was approximately two hundred yards south of his daughter Zlata’s home. All his precious family would be together, including Dora, who would be living with them. Yes, he would build and his sons would help.

And so with the help of Neevtou, Shama and a few carpenters, they built the house in the angle of the road leading to the bridge. The location was perfect – smack in between the two sections of Ostropolye on either side of the river, with the bridge connecting the two. Meyer’s home abutted a large court in front of his balcony. Facing it was the home of his daughter Zlata and son-in-law Yossel (Joseph). It was a nice cottage with beautiful roses growing on each side of the entrance.

Meyer’s home was more or less the same as Neevtou’s. Neevtou’s home was attached to Meyer’s home at right angles, with a large porch overlooking the marketplace. Shama’s home was attached partly to Meyer’s home at the back. Each home had good lighting, built in ovens in clay walls that were very efficient, about twelve feet high, four feet deep and four feet wide.

Shama Kitner, Meyer’s son , was a lucky man. He was fortunate to come back from the Czar’s army unharmed. He was broad shouldered with arms like iron, six feet tall, well muscled, and strong and adept enough to be honoured with a special medal of bravery. He was very well respected by his fellow soldiers, well liked and appreciated for the saving of not one, but two, officers’ lives.

One of the officers presented him with a beautiful silver wine cup adorned with the Russian eagle. The other officer gave him a gift of unusual scissors, made of very good quality steel. These gifts were presented during a special evening of celebration, in honour of Shama’s bravery. The best gift of all was the release of his commitment to the Czar so that he could come home to his family and to his childhood sweetheart Nechuma (Naomi), build his home, marry and start a family.

Moishe (Moses) Echenberg was Nechuma’s father. He was a tall goodlooking man, very muscular, with wide shoulders, piercing large black eyes, and with dark hair and a long dark beard that tapered to grey. He, like his father Zaida Alter, was very religious. He was well respected by the whole village, not only because he was Ostropolye’s commissioner, but because he was involved, with Meyer and Zaida Alter in the establishment and construction of the only synagogue in the area. He was a wonderful provider and a devoted husband and father, besides being loyal to the whole family.

Hanna was sixteen years old when she married Moishe. She was a beautiful woman with a tiny figure, beautiful complexion, and pleasant- looking face. She was always devoted to her large extended family. The oven built into the clay wall of the kitchen was a continuous source of baked goods: fresh bread, cherry and potato verenekes and kiggel and meun (poppy seed) recipes from Humentaschen to honey sweets that melted in your mouth.

They were both believers in education, and all their four girls learned to read and write Hebrew and Yiddish. Their two boys also received the same education. Duddy (David), the eldest son, liked to be immaculately dressed, and fell in love with the beautiful soft leather Russian boots his father had made for him. He vigorously refused to go the Gymnasium (school) because he had to walk on muddy roads and he did not want to get his boots dirty.

They always glistened. His father actually hired a man to carry him to school on his back, because he did not want him, or any of his children, to miss any time in school.

Lusye (Leon) was the younger of the two boys, a very active child, very much involved in school. He was also interested in the garden. As a little boy he watered the flowers with a small pail, and raised pigeons in the attic of the bam. He studied pigeons and knew every species. He enjoyed it when his mother asked him to pick vegetables from the garden, and became the one designated for that task.

Munye, Buzye and Nechuma, the eldest of the children, were three beautiful girls, very intellectual, bright and excellent in their studies. They were very forward thinking, and were responsible community members, helping at the school and during times of sickness.

Reva was the youngest of the family. She was fourteen years younger than Duddy. Excellent in studies and eager to go to school, she was a studious little girl, very quiet at home and being the baby she was loved, cuddled and entertained by all. Very sweet and intelligent, she warmed herself into your heart.

Nechuma had a beautiful face with delicate skin, dark hair, and big dark brown eyes that made you see beyond their physical beauty. Through them you could see that in her heart she was a kind, generous, and loving person.

The three older girls were very popular with the boys and girls in the neighbourhood. They were very devoted to their parents, their family, and contributed more than their share to help the elderly. So much did the sisters sympathize with the plight of the poor, that they joined the small group of intelligentsia in Ostropolye in hopes of creating a wonderful and brave new world. As time went by Munye and Buzye found boyfriends that shared the same beliefs, and so became more and more involved in the Communist movement.

Nechuma, the youngest of the three, was not involved like her sisters, because she was more interested in that young soldier in the Tsar’s army. She was gradually becoming more and more enchanted with Shama Kitner. When a group of teenagers gathered to talk, sing songs, go on hay-rides, or picnics, they found themselves drawn to each other. Shama strove more and more to get leaves from the army. She felt her heart skip when she beheld this handsome young man and looked forward anxiously for his visits.

As the news of the Tsarist government’s instability grew, some in the village grew afraid. Thus Meyer saw his family gradually depart. Neevtou and wife and his family, Yossel and Sonia, decided to leave for a better life in a distant country. It was easy for him to get a passport and proper documents, because of his Father Meyer’s close affiliation with Moishe Echenberg, the commissioner of Ostropolye. They left for the United States of America, much to the disappointment of Meyer and Maita, whose sorrow in seeing their loved ones leave forever was tempered with the hope of what opportunities awaited in the Goldene Medina. They were soon followed by Neevtou’s family. Another blow for Meyer and Maita. However, they derived great pleasure from Shama, who was courting the beautiful Nechuma, daughter of their friends, Moishe and Hanna Echenberg.

Shama was setting himself up in business, in preparation for marriage. The living room in the front of his house was converted into a large watchmaker’s shop with a large window looking onto the front porch. He ingeniously made the large dial on the clock out of plate-glass, with big minute and hour hands. The clock’s mechanism was so small it was hardly noticeable. It looked like there was no clock there, just the two big hands indicating the time.

The clock was the only one of its kind in the village and it was in a prime location. It was in comer of the house Meyer built facing the road going to and from the bridge. In back of this modest shop that eventually grew into a substantial jewellery store was a corridor leading into the very large kitchen in the back. A door on the right wall led into a very large bedroom with a big luxurious bed in the centre facing the entrance. On the wall next to this door was a beautiful silver tray that was made by a well- known Ostropolye sculptor depicting the story of Ivan Ivanovitch, a Russian peasant who tricked Napoleon’s army by leading them into the woods instead guiding them into Moscow.

The oval silver tray was all embossed with a sharp steel nail and showed one of Napoleon’s generals offering a bagful of gold coins at the feet of Ivan Ivanovitch. The story was embossed around the oval tray. The peasant preferred to be shot to death, rather than lead the army out of the woods and towards the road to Moscow.

Opposite this wall, on the right and in the middle, was a round glass set in a brass bezel that opened up into the parallel corridor in Meyer’s house. It was the connecting link between the two families. Underneath this window, which was about twelve inches round like a boat’s porthole, was a black leather couch. There was no ceiling in this hallway connecting the shop and the large kitchen, but a very large skylight that threw sunshine into the house.

The kitchen was very big. The left wall contained the oven, built into the wall. The right wall as you came in contained a few steps that led into a very big room called the Komer, like a large storage area. It was built over the stable, into a sloping hill that ran alongside the road to the right (eastern) side of the building.

It was an ingenious concept that was most likely Shama’s idea, since he was very capable in these matters. It made it very easy to drive into the stable with horse and buggy from the side road, without taking away living space from the house above. On the left wall further away from the oven was a large bathroom, with a toilet complete with chain, unique to the village. There was also a large bath and a window that provided fresh air and light for the bathroom. A back door lead out of the bathroom into the little passage.

The back wall of the kitchen, facing you as you walked into the kitchen from the hallway, was another ingenious invention of Shama’s. It had a false window at the very top near the ceiling. By climbing a ladder to the window, you could push it open by means of a spring hinge, go through, and then climb down the other side into a secret chamber. There you were surrounded with shelves that contained expensive jewels, clocks, watches and other valuable items. This room was built a few years after Shama married and his jewellery store had expanded.

Shama now was courting his love Nechuma almost every night, and when he was overloaded with work, she would come to visit him and keep him company, sitting next to his bench. It was very pleasant for him to do the work he liked so well and with the girl he loved beside him. And so during his free time in the evenings, Shama started to make a gold chain for his future wife, patiently making four rings into one link, and connecting these links by patiently soldering them together, until he had a chain that was approximately thirty-six inches long.

Meyer and Maita Libbe were pleased with Nechuma and her esteemed family, with whom they were already friendly. Because of their involvement in the founding of the synagogue, the Rabbi of the synagogue was honoured to perform the wedding ceremony. However, Nechuma, being modem-minded, would not agree to go to the mikvah. She stated she would not bathe in water other women had used, claiming it was not healthy, much to the disappointment of her parents, as well as Shama’s parents.

Because of that, it was deemed unsuitable to have the wedding in the synagogue. Much to Nechuma’s preference, she and Shama requested to be married in Moishe’s large mill on the outskirts of Ostropolye. It was very spacious and could be cleaned up very easily, decorated nicely and could easily accommodate the large party family and the friends. And so it came to pass that Nechuma realised her wishes. The mill was transformed into a beautiful hall, elaborately decorated with hanging ribbons. The beams were covered with colourful cloth, an platform set up for the klezmers (musicians). The wine was flowing with the merriment of everyone and the mood was high. The food was delicious and both mothers, Hannah and Libba, added to the tables their dishes they were renowned for.

Although it was unusual to hold a wedding outside the synagogue, it was a great success. The music resounded merrily through the hall and everyone danced and drank into the early morning. All their remaining relatives were there. Shama’s friends including Yosef Pugach and Shmielick Echenberg, his buddies from the army, and the chief of police was there. He was more than a chief of police: he ran the village, like a mayor and chief of police combined.

The wedding lasted until early morning and all had a great time. It was a good idea, because the synagogue could never have accommodated all of the guests. It was the most outstanding wedding of Ostropolye, the biggest in the Jewish community, and the first one to be conducted outside the synagogue. Nechuma and Shama moved into their home, the house that Meyer built with Shama, to build their lives together.

Since they were always together, Nechuma watched Shama consistently as he dismantled watches and remounted timepieces with great precision. She started to learn the trade, working together with Shama to become better and better. Gradually the business progressed and became more profitable to the point where his walls were full of nice watches and clocks. That’s when he built the secret wall built in the back of the kitchen to hide he kept his excess inventory. Shama used to go to Kiev for his purchases, and this hiding place served more or less as a vault.

Because Nechuma was familiar with the business, it was easier for Shama to leave for a few days to Kiev. He would come back with the latest in jewellery, watches and clocks and their workshop flourished. He would also come back with rare gifts for Nechuma and family, as well as with stories from the big city.

On one occasion he told the story of a bearded man that ran up to him on the busiest street comer of Kiev and pulled out of the inner part of his coat the most beautiful sable hat you ever saw!

“This beautiful hat can be yours for one hundred roubles,” he said.

Shama took the hat in his hand, felt the soft shiny sable, admiring the lining and fur, and in his head he said, “This hat is a give-away for one hundred roubles -1 must buy it.”

But before he had a chance to bring his money out, a young man ran over, grabbed the hat out of his hand and said to the bearded salesman, “How much for this hat?”

“One hundred roubles,” the man answered, and in the flash of a minute he said, “I’ll take it!” and he handed the money to the salesman with the beard.

Shama was left standing, disappointed.

“Don’t worry”, the man exclaimed, and with that he pulled out of his inner vest pocket a big gold pocket watch with an elaborate gold chain.

“You can have this prize for only three hundred roubles. Its value is more than one thousand roubles.”

Shama took the watch and chain in his hand, and immediately realized it was a fake.

“No thank you,” he said, rejecting the salesman’s insistence.

Every time he went to Kiev and passed the same or nearby comer, he saw the same bearded man selling the sable hat, and the young man quickly buying it in exactly the same way.

Shama and Nechuma were married in 1909. Before Shama married Nechuma he knew that she was bom with a murmur in her heart, and had to be careful of over exertion. However, being newly married, they consulted a doctor for the possibility of starting a family. The doctor stunned them with the news that Nechuma’s life would be in danger if she had a baby. The following year they both went to Kiev and sought out a heart specialist only to be given the same sad news. As the years went by Nechuma found her lives empty without a baby. She decided on her own to take the chance, in spite of the doctors’ warning. She took the matter in her own hands, and with the blessing of God, she became pregnant in the fall of the year 1913.

Shama also as a sideline dabbled in stocks. In that era, when you purchased stock, you purchased the actual merchandise, whether it was a carload of copper, flour or whatever. Shama’s very good friend was Yossel Pugach, who came from a wealthy family, but he himself was not a businessman or a craftsman. He was a very well educated young man, interested in history, astronomy, etc. Shama and he both pooled their resources and purchased stock together, and shared the profits or losses.

On one of the occasions that Shama left for Kiev, Yossel Pugach purchased a carload of honey while Shama was away. This time Shama was delayed in Kiev and stayed longer than usual. In the meantime, the carload of honey kept going down and down in value every day and Yossel got nervous and figured its best to sell it even at a loss of 25,000 roubles.

When Shama came back, he did not tell him about the purchase, or the sale. When Shama found out about the incident he asked Yossel, “Why didn’t you tell me you acquired a carload of honey when I was in Kiev?”

“Because,” Yossel replied, “I did not have a chance to ask for your opinion when I bought it and took upon myself to sell it at a loss of 25,000 roubles.”

“Tell me honestly,” said Shama, “If you would have made 25,000 roubles, would you have split it with me?”

“Of course,” said Yossel.

”So then”, said Shama, “It is only fair that being your partner, I should also share half the loss.”

This was how business was done in that era. Deals were struck with a handshake, and one’s word was a holy commitment to be kept.

Other members of the Kitner family decided to pull up stakes and depart for the new world. Dora made her decision to leave with Yossel Tretiak and her mother Maita for America. Neevtou and his wife, K., with his little son Yossel and daughter Sonia were also leaving. The Kitner family was being dispersed, and it took is toll on Meyer. They decided to leave as most of the family were excited to leave, and one convinced the other. It was easy to get the documents from Moishe Echenberg, but they could not convince Shama and Nechuma.

Shama had more invested in Ostropolye than his did sisters or brother. His home was precious to him. The jewellery shop business that he built was dear to him. He had worked very hard to build this foundation. Mostly, he felt secure. The Chief of Police was a very good friend of the family, and especially of Shama, and he laughed at the talk of change in the government.

It would never happen, according to him. The Czar’s Imperial government was too powerful. His army was well equipped, well trained, well fed and well armed.

Nechuma’s elder sisters, Munye and Buzye, close to her in age, really believed in Communism. They and many of their friends, the new generation, wanted to reach out to the people. They chose the benefits of Communism over the faults of imperialism: high taxes, preferential treatment of the elite, corruption among the politicians, the aristocracy, the royal family, and others.

It was hard to leave Ostropolye, to leave your friends, the village where you were bom, the market, the synagogue, and the community that you knew by their first names. After all, although Shama’s family was leaving, Nechuma’s was still there: her three sisters, her two brothers, her grandfather Zaida Alter and her loving father Moishe and mother Hanna.

They too were set on remaining. Moishe the commissioner was busier than ever, as some people were starting to leave. Zaida Alter was busy in the egg business with Munye and Buzye living under the same roof. Reva, under the wings of her parents, loved school, was loved by all. Lusye, happy in school was outstanding in the Hebrew studies, and very happy raising his pigeons.

Duddy, fourteen years older than Reva, had ideas of his own. He was the only one in that family that believed in starting his life in a new progressive country like America. He was a very popular young man, very handsome with a muscular agile body, very dark brown eyes and a head full of curly hair, an admirable ice skater, who took every opportunity to demonstrate his skills on the spacious river nearby. Even though he his family and many friends in Ostropolye, he made the decision to leave shortly after he finished at the Gymnasium.

Everyone was very sad when he said goodbye, and wished him well in the new country. Moishe gave him a generous amount of money that would help him to get started. His goal was Montreal, in the country of his choice,

Canada. His mother Hanna helped him pack his beautiful clothes and quality leather boots, with tears.

|

Ostropolya, circa 1910: Shama Kitner, center back row, Nechuma Kitner second to the right, Alter Echenberg, sitting with white beard, Moses, sitting with dark beard, Leon centre front row, Reva right front row.

By Deborah Sheppard

August 26, 2001

In memory of Myer

You were our bridge

to the world of village,

orchard, river,

the last one to remember,

to remind us of

the long-ago journey that

brings us all

to this place,

here, in this moment.

Our palms are cupped

to hold all

the stories of boyhood,

daredevil little one,

triumphant vaulter,

memories of the man –

friend, cousin, uncle,

hus band, brother,

grandfather, father –

heart big enough to hold

each one of us,

uncounted acts of

gentle kindness that glisten,

gems we string together to measure the length of

your rich and loving life.

Tsitsinye

By Leon Echenberg (as retold by Peter Tannenbaum)

Throughout most of his adult life, Moses Echenberg, son of Alter, was the chief magistrate of the Jewish population in the shtetl of Ostropolye in the Volinye province of Tsarist Russia, in what is now within the Ukraine. It fell to him to intervene with the local authorities on any issues that affected the Jews of Ostropolye. He was a proud man, with an iron will and a fierce temperament. This made him ideally suited to deal with the local constabulary, and he was well respected by them.

In one critical matter his influence was crucial. Every year recruiters from the Tsar’s army came — known colloquially as khuppers — and fingered all those eligible, which meant any young man not already enlisted, for enrolment into the ranks of the army. For young Jews, this was a catastrophe. Enlistment into the Tsar’s army was a twenty-five year commitment. Once removed from their homes, Jewish recruits were weaned away from their religion and culture, and lost all connection with their families.

Thus it was not surprising that each winter, when the khuppers came calling, young Jewish men mysteriously disappeared. In the local jargon they were referred to as chichiks – chickadees – who flew the coop at the first sign of danger. If a chichik was unfortunate enough to be caught, the only recourse was a substantial bribe to be paid by their family to the authorities. And it was in this regard that Moses was often called upon to serve in the capacity of negotiator. 3

One such instance involved Moses’ benighted young cousin Yitzik. Despite the evident risk of being out and about during the dangerous enlistment period, Yitzik decided to pay a visit to his cousin Moses, thinking to sneak in through the back entrance, so as not to be seen.

The front room of the house, one of the grandest in the village, served as Moses’ “office” where he received local dignitaries and members of the Jewish community to discuss matters of business. It was there in this room that the local police chief happened to be awaiting Moses’ return when, through the side window, he espied the unfortunate Yitzik attempting to sneak in through the back.

Not wasting a moment the Police Chief tore through the house and grabbed Yitzik as he made his entrance. He stuck his forefinger through the top buttonhole of Yiztik’s winter coat in order to firmly secure him.

“Now, I’ve got you!”, he cried triumphantly, and dragged him to the front room.

At the moment Moses arrived. Taking in the scene, he understood in an instant what was happening. His face immediately clouded over, and his temper broke like a furious thunderstorm. Lashing out with his fist, he landed a tremendous blow on the Police Chiefs hand that landed on the offending finger that held poor Yitzik captive, causing the Police Chief to relinquish his hold. He clutched his throbbing hand and grimaced in pain.

“Alter-ovich!”, he exclaimed, calling Moses by his patronym in the Russian vernacular. “What gives?” He was astonished, never expecting such behaviour from his good friend and colleague.

Moses glared angrily at the Police Chief and pointed to the door.

“Get out!”, he roared. “How dare you do this? In my house? To my kin? Don’t you ever do anything like that again!”

As soon as Cousin Yitzik found himself out of the Chiefs clutches, he beat a hasty retreat, as you can imagine.

Some years later, Moses was stricken by a terrible stomach illness that would cause him to take to his bed for days at a time in excruciating pain. On one such night, at three o’clock in the morning, his household was awakened by frantic pounding at the door. Who could it be at such a late hour?

It was Tsitsinye, the miller’s wife. Now, being the miller’s wife was not something to be proud of in the caste-ridden world of the nineteenth and early twentieth century Jewish shtetl of Eastern Europe. They were reputed to be gonifs, crooks. In the winter, when the farmers would bring their grain to market to be milled, Tsitsinye would hock her services in a loud, grating voice. To keep warm, she clasped a great earthenware pot to her belly, filled with the burning embers of roasting wheat chaff. It was said that the millers secretly siphoned off some of the farmer’s grain, secretly stealing from them. Thus they were relegated to the bottom of the social pecking order.

And here was such a one – Tsitsinye – pleading for Moses’ aid. Her son had been seized by the khuppers. What was she going to do? To everyone’s great surprise, Moses rose in great pain from his sick bed, donned his clothing and went out into the cold, bitter night to attend to this situation. He was out all night long, returning only in the morning, ashen-faced and wracked with pain. He immediately took to his bed.

That evening, after he had slept and eaten a little, his young son Lusye came to visit his bedside.

“Father,” he said. “I don’t understand. Tsitsinye is the lowest of the low. Why, of all people, would you go and help her, when you are so sick and suffer so much? Why, Father, Why?”

“I’ll explain to why, my son,” replied Moses. And he told Lusye the following story.

Twenty years earlier, when Moses’ wife Rachel was heavily pregnant with their first child, Lusye’s older brother David, she ran a dry goods store in the market place. It was winter, and the khuppers had already made their rounds, seizing mostly non-Jewish youths. That meant that there were crowds of young Goyim milling around the market place looking for trouble.

Once chosen for the army, these young hoodlums could act with a great deal of impunity, knowing that the local authorities would turn a blind eye, preferring to see these miscreants ushered into the army barracks than languishing in a jail cell. Thus they were allowed to run riot. This was a bad time for the Jews who were often targeted by these thugs.

A group of twenty or more of them had gathered that day and ransacked Rachel’s shop, leaving her in a hysterical state. Moses arrived soon thereafter, and seeing the shambles and his poor wife distraught, immediately lost his temper and ran outside to confront the attackers who were still milling around in the street. Although he let fly many telling blows, at twenty to one the odds against him were too great, and Moses was dragged away by the mob.

They took him down to the banks of the river, where they intended to beat him to death. They chose a spot at the bottom of the clay cliff, where they thought they would not be seen. But at the top of the cliff, on the road on her way to the market that day with her earthenware pot filled with red-hot embers, was Tsitsinye. She looked down and saw what was transpiring. Without a second’s hesitation she tipped over that earthenware pot, sending the scalding embers tumbling down onto the heads of the young ruffians.

They scattered like leaves in the wind. She saved Moses’ life that day. That is why twenty years later, he rose from his sick bed to return the favour.

Leon’s Winter Boots

By Anne Linds Echenberg

During the war of 1914-18, Leon was a youth of nine years. His father was ill, food was scarce as were wood and fuel. At this point there was typhoid fever in their home, the only two who were not ill were Leon and Reva, two years younger. It was winter and it was very cold, so the two children went out with a small child’s wagon which they both pulled.

Reva dressed in her Mother’s fur jacket which came down to her ankles and Leon with his winter boots. They managed to find some wood, pieces of coal and roots from the gardens. Leon wore his wonderful boots for six months, never taking them off for fear of tearing them if he had to pull them off each night. When he finally was able to remove them, his poor legs were white and thin. It took months before they healed. Poor kid!

Ready for Passover

By Hope Echenberg Finestone

My Dad’s grandfather, Zeda Alter was a pious man. So it is understandable that the holiday rituals would have been carried out religiously in Ostropol. My Dad never failed to recount this story each Passover as my maternal grandmother, Bessie Linds, did her preparations.

All cooking and eating utensils had to be kashered (made Kosher) to be utilized for Passover. Dad remembered the silverware in particular was polished and rinsed. Then each piece was tied to a long cord and dipped into boiling water into which a very hot piece of iron was dropped.

Without fail, Zeda Alter would advise Dad and his younger sister Reva that their mouths needed to be kashered for Pesach too. He would line them up with their eyes closed and their mouths wide open. Anticipating a hot piece of iron, they were so relieved to feel something cold and refreshing on their tongues. Zeda Alter placed an orange cube in their mouth, a special treat he acquired while traveling to Kiev.

Ostropolye Now

By Sharon M. Weinstein

I: The Journey

Father Ken Nowakowski, president of Caritas Ukraine and Rabbi Reuben Azman, of the Great Synagogue of Kyiv, arranged for my visit to the Echenberg homeland. They assigned a multilingual driver named Tolik who was fluent in Russian, Ukrainian, English, German, and Polish.

I met Tolik in Kyiv, where I had convened meetings with Rabbi Bleich of the Orthodox Synagogue, and Rabbi Azman, of the Great Synagogue.

Kyiv is home to Babi Yar, a ravine in which 100,000 Jews, Communists, and POWs were killed in Sonderkommando 4a of Einszatzgruppe C. I have been to Kyiv many times in the past nine years; I have always disliked visits to Babi Yar. Tolik and I began our journey from Kyiv to the Echenberg city of origin at 7 a.m.. on a wet, foggy day. We headed southwest, anticipating a four-hour trip by car.

The road from Kyiv was not yet crowded with commuters, and we left the city limits without difficulty. Ukraine is comprised of 60+ oblasts, similar to states or provinces. Each of the Oblasts has villages, cities, and towns. The local demographics of each vary considerably. I had reviewed Dean’s notes the previous evening, and I was well prepared for the trip.

I was assigned the role of navigator, and Tolik gave me the Russian/Ukrainian language map to read. With the Kmelnitski Oblast as our target, we headed toward the city of Starokonstantinov (Old Konstantinov).

II: Zhitomir

We stopped at a local apothecary along the way in the city of Zhitomir. Not trusting the cash register, the clerk checked her figures with an abacus, similar to the patterns of 1990 USSR. Zhitomer was once the home of hundreds of thousands of Jewish citizens. Although a synagogue, holocaust museum, and cemetery remain, the Jewish population now numbers 2,000 persons. Zhitomer served as an Army base during the war. There were many Soviet-style buildings, in stark contrast to modern-day Kyiv. Tolik pointed out the local administration building, which was graced by one of the few remaining statues of Lenin. After completing our purchases, we headed west once again.

Tolik talked about his life in Lviv. He said that he had been a national swimming champion. His instructor in Lviv was Gregori Mikhael Weinstein, who at age 55, left for Haifa. His other instructor, Vira Lipman, now resides in Tel Aviv. The city of Lviv (in Ukrainian) or Lvov (Russian) in southeastern Poland was occupied by the Soviet Union in 1939, under the terms of the German-Soviet Pact. Lviv was subsequently occupied by Germany after the invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941. In November 1941, the Germans established a ghetto in the northern sector of the city. Thousands of Jews were killed in the ghetto and in the Belzec killing center.

As we traveled, we passed a magnificent birch forest. Nazis had occupied the area during the war. During Soviet times, if you had a fruit and produce garden, you paid taxes on the quantity of fruit your garden produced.

We drove through Chedani; the name of the town means ‘miracle’ city. We shared the highway with horse-drawn wagons and carriages, and saw very few cars. Tolik offered some geographic boundaries. Ostropol was 50 km to the Austria-Hungarian territory during the time that our ancestors lived there; it is now 1400 km to the town of Brody, where many egg exchanges occurred. Tolik suggested that egg exchanges might have been in violation of local law. The town of Luba was our next stop; Luba is the home of the Roman Catholic Church and the Caritas Center. Residents have received substantial aid from the U.S.. and Canadian governments. We approached a stop sign that was in English, rather than Russian. It marked a traffic circle and a main intersection. Chickens, roosters, and geese crossed the intersection quite slowly. Tolik pointed out a flourmill that is still in use; it was as if time had stood still in Luba. He also showed me the Transfiguration Church.

Ill: Volhvnia

In Volhynia, more than 142,000 Jews were murdered between May and December 1942. Some, who had been given refuge in Polish homes, were murdered along with their Polish protectors in the spring of 1943. In many villages, Poles and Jews fought together against the Nazis.

As we approached the Kmelnitski zone, we were greeted by a dull green tank. The words inscribed in front of the tank were: “Who set them free for the good of Ostropol.”

Traveling throughout the region, we searched for Kalinin Street in Staryostropol. We passed the main administrative building, a school (where Dean had visited), and the central bus stop. Stopping to ask several people along the route, we were directed to a fork in the road. Just west of Slobodah village and Adampil (town of Adam), we found a music school and a post office. Tolik entered the post office and asked a customer for directions. He returned to the car accompanied by Victor Sergeivitch Gorbachuk, who led the way to our destination. Victor Sergeivitch told us that mail is delivered on Wednesdays and Saturdays. It costs 4 hgryna to send a letter to the U.S.., and the monthly pension is only 45 hgryna, from which utilities must be paid and groceries must be purchased. He also said that in 1959, there were 10,000 people in the district; the current population is less than 2,000. He pointed out a small hospital, four stories high and Stalinesque in style. Apparently, there are two physicians in the area. Originally opened as a 100-bed hospital, there are now twenty staffed beds.

Turning onto a cobblestone road, we saw the mud-covered Kalinin Street sign and we approached the home of Anatoly Polansky and his wife, Katerina (Katya).

Anatoly said that he had been eagerly waiting for us. He greeted us warmly, and led us through the outer yard to a pile of shavings, currently used as a doormat. After scraping the mud from our boots, Tolik and I entered the vestibule of the modest home. The cold, dampness, and lack of light did not matter because the light shining from Anatoly’s eyes was enough to warm the entire room. Anatoly is 69, and his wife is 60. They have been married for nearly 20 years. His first wife was Jewish; Katya is Orthodox Ukrainian.

He led us to his desk, and immediately spoke lovingly of his visit with Dean five years ago. He had written a letter to me, in which he described his current situation. Tolik translated it onsite.

“My name is Anatoly Ostropovich Polansky. I ask to describe my situation in which I permanently care for the Jewish cemetery and guard it from vandals. I took this responsibility on my own. I am the only Jew in Ostropol. Soldiers killed as many Jews as they could locate in 1942. All of remaining Jews moved after that time. The local authorities take care of only orthodox cemeteries (Greek and Roman Catholic). No one takes care of Jewish cemeteries except me.

In 1997, Dean Echenberg came and promised to support me financially for my activities. He was contacting with the Peace Corps where he registered the necessary documents. The documents said that Polansky would be receiving $15.00 per month and a one-time payment of $100.00 for his (my) work. The manager of the office, Bob (Robert) called me and invited me to his office where I met with him. Thanks to an interpreter, I understood him and he gave me all necessary documents to sign. Those documents were about money and wages. He did not give me a copy of the documents. I read them and signed them over 5 years ago. Russian people say, “if there would be some honoraria for his work, it would be appreciated and would support my poor status.”

In spite of all this, I am still believe that Jewish people lived properly, and will be cared for properly when they die. I am working for the principle and means without bread. These people, in spite of their death, deserve my care. Now, I need an operation. I have adenoma. I did not have the surgery yet because I have not enough money, and for other reasons I can tell about. One year ago, when I was ready to go to the hospital, my son, Ihor, died in the Russian war, and I had to use the money to go to Moscow to return his body to this region.”

Anatoly and I discussed his need for surgery, and whether or not the local hospital could provide it. He told me that the main hospital in Stantinokov would do it for 700 hgyma or $140.00 (including the doctor bill and all medicines). He said that he has several bottles of heart medicine, including cardiodine, validol, and others. He takes what sounds like nitroglycerin as needed. He said that Dean had given him $60.00 during his visit, but of course, it was gone a long time ago. I gave him a total of $630.00 in cash; $150.00 for the surgery, $100.00 wages (honoraria), and $15.00 per month for two years. He was surprised, but so very pleased. He turned his head and you could see that he was shielding his tears from my sight. He and Katya embraced me and held me tightly.

The Polanskys survive on a $25.00 monthly pension and food parcels that he travels to Kmelnitski City to obtain from Chessed Beth. They grow potatoes, fruit and some other vegetables in their yard. Polansky then led Tolik and me to the cemetery sites while Katya prepared tea. Polansky has served as cemetery caretaker since the death of his Uncle, Avram Lessek.

Lessek was responsible for the engravings on the stones, many of which had eroded with age. He lived on the grounds of old (starry) cemetery; the Nazis took his house and he was killed at gunpoint in 1942. Polansky erected a brick fence around the old cemetery. Neighbors took the bricks, and parts of the remaining headstones to construct their own homes. He has asked neighbors not to let their animals roam throughout the cemetery, and according to him, “no one listens and no one has respect for the dead.”

We walked from one end to the other; he pointed out where people, including our ancestors, who died prior to 1909, would have been buried. He estimated that 10,000 bodies were buried in the area. He also showed us the burial ground of his grandparents, and the rabbi of the community.

We then crossed the road to the new (novy) cemetery, adjacent to the Polansky home. He had erected a fence to surround and protect the property. Although it was a cold winter day, you could see that plantings and trees added beauty to the site. He recently expanded the burial area; there are 400 bodies at present, including those of his parents. He has a small dacha-like building where he keeps his supplies. He also has a plank of wood laid across two large rocks on which he sits to reflect on his work during the warm weather. It is a source of peace for him because when he is there, no one can see him or hear him or his thoughts.

We returned to the home that he had built with his bare hands. Trained as a carpenter, he was employed as a driver for the Germans during the war. As a Jew, he was given the oldest, most unreliable car to drive. We washed our hands and sat down for tea. Katya had prepared plates of her own pickles, perogi, walnuts, and tea. We enjoyed homemade wine and home-distilled vodka, and we shared stories about our families. Polansky told me that there were two “Weinstein” families in the Ostropol region. They left prior to the Nazi invasion. Their relatives were buried in the old cemetery. He asked if I might be related to them, and of course, I did not know. He wrote a letter to Dean, with whom he was very impressed. I plan to send the translated version to him next week.

We remained with the Polanskys for photos, more stories, and camaraderie for several more hours. We agreed to take a 50 pound bag of potatoes, carrots and apples from their garden to Anatoly’s sister in Lviv. She has breast cancer, and she recently lost her daughter and son-in-law. She is caring for a one-year old grandchild alone. Polansky hoped that we might locate some used clothing for the child. I promised nothing, but I planned to pursue the purchase of clothing when I arrived in Lviv on the 21st. We hugged and kissed like old friends who had recently been reunited after many years’ absence. I felt as if I was truly ‘with family.’ Polansky asked me if all of the Echenbergs were ‘so warm and wonderful.’ I replied that not only were the original Echenbergs wonderful, but so too were those who joined the family through marriage.

Tolik and I re-arranged the car to make room for the potatoes and fruit. Anatoly and Katya accompanied us to the car and gave us a bag of walnuts for our journey. It has started to snow lightly, and the white flakes on Anatoly’s red face created a wonderful sight. We then departed for Temipol and the Caritas guesthouse, our overnight accommodation.

We encountered a severe snowstorm along the way, making the road slippery and travel difficult. Snow is not removed form the roads; there is no budget for snow removal and no equipment. The local officials believe that after several cars pass, the road will clear somewhat.

IV: Temipol

Because of the storm, we arrived in Temipol two hours later than expected. The guesthouse, home to an orphanage and other Caritas programs, had five guestrooms, no heat, and no hot water. We lit a fire in the main living room, and sat there with pots of tea to remove the chill from our wet, cold bodies. I planned to gather as many blankets as possible for what promised to be a very cold night.

Despite the cold, I felt warm within. The day had been long, but wonderful. My visit to Ostropol was a moving experience, and one that I shall not soon forget. In my work in the former Soviet Union over the past nine years, I have been a part of many life experiences. I have witnessed birth, death, surgery, and illness. I have met and known some very wonderful human beings, and the Polanskys clearly earned a place among the very best. We are fortunate to have them caring for the cemetery and home of our ancestors in the former Ostropol region. They now have money to last forawhile. Some of it, I’m certain, will be used to visit his sister in Lviv and to make plans for the care of her grandchild when she is gone.

I plan to communicate with Anatoly in Russian by e-mail to Caritas Ukraine. They have promised to download the letter, and mail it from Lviv to Staryostropol. I want to follow up with Anatoly about his surgery and his plans for a physician visit. I want them to know that the Echenbergs are their friends and that we value what they have done and will continue to do in the homeland of our forefathers.

V: Postnotes

Anatoly’s sister died two years later; she received care in the Lviv Clinical Oblast Hospital under the direction of one of my colleagues, the chief physician.

I sent follow-up letters via mail through Caritas, Ukraine on an annual basis through 2005 when my work in that region decreased and when Father Ken was transferred to Ottawa. Management and oversight of Caritas Ukraine changed substantially, but Tolik, who remains, told me that the child had been cared for by other very distant family members.

An additional $400 was transferred to Polansky through my contacts at Caritas Ukraine.

One Way Ticket

By Peter Tannenbaum

One of the last groups of Echenbergs to emigrate from Ostropolye to Sherbrooke consisted of the widower Alter Echenberg, his grand-daughter Nechuma Kitner with her husband Shama, himself a distant cousin, their two boys Meyer, aged six and Mussie, just an infant. Also accompanying them were Nechuma’s two youngest siblings: Lusye, a boy fifteen years old, and Reva, her twelve-year-old sister.

It was an arduous journey across the Ukraine, Poland and Germany to Antwerp, and then finally by boat across the Atlantic to Halifax, Nova Scotia. By the time they arrived in Canada, they had been travelling more than a year. Their brother David Echenberg had preceded them years before, and having established himself among his landsmen in Sherbrooke, had been instrumental in sponsoring his family’s immigration to Canada.

He therefore travelled from Sherbrooke to Halifax in order to greet them upon their arrival. It was 1921, the year his daughter Ruth was bom, and in those days the train trip from Montreal was more arduous, taking up to a week to accomplish. With great anticipation he arrived at the pier in Halifax as the ship bearing his grandfather Alter, his siblings, brother-in-law and nephews came to dock.

On board too, the family felt great anticipation. But there was trouble. Shama had come down with a rasping cough, and was diagnosed with influenza. He was deemed unfit to enter Canada, and was told by the immigration officials that he would have to return to Europe.

“Well, if my husband is going back,” cried Nechuma, “then so am I and my babies with me!”

“And if my grand-daughter isn’t staying,” declared Alter, “then neither am I!”

Naturally there was no question of letting young Lusye and Reva disembark on their own. It looked as if the whole family wouldn’t make it ashore after all.

Back on the pier, David watched anxiously as the passengers deboarded. One after the other, he looked into their faces in the hopes of recognizing his long lost family. Nothing! No sign of them at all! He was beside himself with worry. Where could they be? It was now a long time since the last passengers had left. Were they still on board? Could they have missed the boat? He began to pace up and down the pier frantically.

Suddenly he heard his name shouted out. “Hey, Mr. Echenberg! What are you doing here?”

He looked up to see a customs official striding towards him with open hand. It was a colleague from his early days in America, when he worked for a chandler in New York City, loading goods onto ships. He had often dealt with this gentleman. What a coincidence! Imagine meeting this man here, of all times, of all places!

David quickly told his story to his friend, the customs officer, who listened attentively.

“Let me look into it,” he said when David finished. “I’m sure there’s some explanation.”

He boarded the ship and after a long, long while that seemed to last forever, reappeared and came down the gangplank to where David was waiting. He explained the situation to David.

“So, what can I do?”, exclaimed David.

“Do you have ten dollars on you?”, asked the man. “I’ll pass it to the medical officer who examined your brother-in-law. That should take care of it.”

Ten dollars was a lot of money in those days, more than a week’s wages. David willingly handed over the money and watched anxiously as his friend disappeared once more into the bowels of the ship. In the interim, the family had been herded into a holding area where they awaited the outcome. Leon, as Lusye was later known, remembered seeing a man in uniform slouched on a bench, chewing and chewing and chewing, but never swallowing. He was fascinated by this. He couldn’t understand it. What happened to the food in this man’s mouth? Of course, he had never heard of chewing gum.

Finally the situation was resolved. Alter, Nechuma, Shama et al were ushered into the welcoming and relieved embrace of brother David. They travelled back to Sherbrooke together where they were received like royalty by their long lost relatives

A Difficult Beginning and Easier Endings

By Jackie Smith Friedman

Background

My mother and father were both bom in Ostropolye (in Villini Gabemi) in 1911 and 1900 respectively.

Mother’s Background

My mother’s family was well established and was considered well to do. Her maternal grandmother Billya was owner and “CEO” of the only mill in town. The home of my grandparents was furnished opulently. The interior described as “being in Paris”. There were servants attending the household.

Because her parents were barren for fifteen years, there was great celebration when a son was bom. Money was handed out in the streets to the needy. Joy abounded when two years later my mother was bom. Her early childhood was uneventful although she told of almost drowning when her father took her swimming in near by rapids and she let go of the chain she was told to hold. A big celebration followed.

At the age of six, the first of many tragedies befell my mother. She caught smallpox, which was transmitted to her mother, who died from the disease. Two years later, the Bolsheviks marched into the family home and shot her father before her eyes. She told of begging the soldiers to shoot her instead and of the looting of the house by the so-called loyal servants. My mother and her brother were sent to live from home to home. They lived with aging grandparents, aunts, and uncles.

My mother’s uncle (maternal brother) was sent to study in England. He became an important translator of Russian literature and a member of the infamous Bloomsbury gang in London. His intimate friends were H.G. Wells, D.H. Lawrence (whose manuscript of Sons and Lovers he had published while the author was out of the country), James Stevens, James Joyce, Aldous and Julian Huxley, and Virginia Wolfe were among his intimates.

Throughout the war years, my mother sent packages of food and clothing to her uncle. He and his friends were sustained by these. H.G. Wells’ granddaughter- Catherine Stoye and I became pen pals. We have met in person several times during the passing years. This family was like family to my mother’s uncle S.S. Kotiliansky.

My mother’s uncle Samuel (Kot) remained a bachelor all of his life. He thought it wise to send the orphan children from the Ukraine to live with his brother Moshe in Montreal. The first attempt failed as passage paid for was never legitimized. On the second attempt in the fall of 1927, the teenagers stopped in London for a few hours where they met their uncle for the first time.

A second tragedy struck when a few days after arriving in Montreal my mother’s brother Eli drowned in a bathtub. He was asphyxiated by carbon monoxide escaping from a hot water heater in the bathroom.

Life was not easy for my mother at her uncle’s home. Her arrival displaced her cousin’s “only child status” and there was rivalry. After a few years at school, my mother went to work, sensitive to her uncle’s struggle as a custom peddler, out with horse and buggy in all weather. She made this decision on her own to the surprise of her family members.

My Father’s Background

My father was bom the last child of Joseph Smith’s second marriage to Michele. At the time of his birth, my grandfather was seventy-five years old. His half sibling, Leah, married Moshe Echenberg and their offspring (Bertha, Becky, Bessy, Sam and Abe my fathers cousins) were all older than my father. Life in Ostropole was a struggle. My grandfather was a deliverer of fish and meat. My father had worked for my mother’s family. He told stories of delivering meat and lobster to the estate of the landlord of the district.

Because he was charming and cute, the woman with all the keys allowed him to visit the kitchen, which he described as being an amazing experience. My father, his parents, and two siblings immigrated to Canada, arriving in Montreal and moving to Sherbrooke in early 1917.

Soon after my mother’s arrival in Montreal, my father went to her uncle’s home with a package to be dropped off that someone would take to Ostropole. My father saw a beautiful blond and blue eyed teenager (sixteen) and he waited five years for her to mature. They then married.

My father was bright, energetic, and young when he came to Canada. He was a sole support of his aging parents and siblings. He began to work wherever he could- custom peddling, clerk at Echenbergs furniture store. He soon realized that he too could be a storeowner and he opened stores in Thetford Mines, Coaticook, Kateville, Stanstead, and environs. Before long, in 1930 he opened a men’s clothing store on Wellington Street, which he owned and operated for thirty-seven years.

My father spoke of pogroms in Russia and how some young men even shot themselves in the foot to avoid army service. His father, an observant Jew wore a kittle and yamilka. He was the butt of name-calling and stone throwing from kids on the streets of Montreal and Sherbrooke. My father’s natural acumen allowed him to succeed in his endeavors. I recall car trips to Rock Island, Vermont with my brother Marvin. We would go with an empty car and the return trip found the car filled with what is so popular today, blue denim overalls, and the two children stretch out lying atop a pile of clothing that filled the trunk and back seats of the car.

My father was active and well liked in both the Jewish and Non-Jewish communities. He was a mason, belonged to B’nai Brith, and the president of Agouda Achim Synagogue for over thirty years. Visiting rabbis and dignitaries often came to our home and my mother was always a proud hostess. My father spoke Russian, Yiddish, French, and English fluently. When he retired and moved to Montreal in 1967, he was already emerged in the stock market and mortgage business. Unfortunately, he died just two years later in June of 1969.

Life in Sherbrooke

I was bom in 1935, a year after my parents’ marriage. My brother Marvin followed fourteen months later. Eric was bom eight years later and my sister Sharon eight years after that.

Life in Sherbrooke was active. The Jewish community (60 families at its peak) was a social one. Men and ladies often met to play cards. The women were homemakers in the morning got dressed up for their daily afternoon stroll downtown. Following my mother’s example, we all worked in my father’s store on weekends and holidays. This continued right through university.

Education was a must in our family and we all obtained graduate degrees. Rice Beach was a great communal Sunday picnic spot. Later, in 1942, my parents built a cottage on Little Lake Magog. Happy times and fond memories abound and luckily my sister and her husband Neil now own and enjoy “the lake”.

My mother was to face two more tragic events in her life. My father died of a heart attack in 1969 and my brother Eric in 1991. These events haunted her the rest of her days. My mother’s great fortitude, inner strength, courage, and adaptability helped her through a long widowhood. These traits helped her confront her own terminal illness. My mother was a remarkable woman, deeply caring for her immediate family and fiercely proud of them and their offspring. She was very independent and in my eyes possessed of a noble presence and great beauty.

My mother once told me that some people have “difficult beginnings and easier endings”- such was her lot.

Grandfather’s Table

By Ruth Echenberg Tannenbaum

In the old country, once a week people would come to see my paternal grandfather, Moses Echenberg, who was the elected leader of the community for more than twenty years. In Sherbrooke, it was my maternal grandfather, also named Moses Echenberg, who was consulted in the same manner. A whole parade of community members, relatives and others, would come calling on my grandfather at the house at Five Prospect Street. A conclave of five, six or seven people would sit in his living room around the oak table and discuss community affairs. Or people would come to him individually about their problems. He became a Justice of the Peace in order to be able to carry out certain notarial functions, such as witnessing the signing of contracts.

Many wonderful characters would come to see my grandfather. One of my duties, when my grandfather received visitors, was to serve a small collation whenever it was called for. “Ruthie, bring me Eier Kichlich (‘egg cake’) mit Schnapps ”, he would say. Or I would bring out a bottle of Scotch with shot glasses. The discussion was always in Yiddish, and although I couldn’t understand, I still got a sense of the qualities and characteristics of the lives of those who sat at my grandfather’s table. My father would often make comments to me afterwards, in private.

One of these wonderful characters was my uncle Max Weinstein. His wife was my grandfather’s sister Sarah, known as Baptsie. It was her son Sam who went to Boston during the depression. He had worked at Echenberg Brothers with the other children of Baptsie. He married Rose Factoroff in Boston. She was the one who eventually introduced Ida to Abe. But to get back to Max Weinstein.

He was a short, stocky man with a big head. He had a full head of curly hair, cut short. His face was deeply ridged and creased and he had a big nose. He had a voice to match his big, heavy face. He gurgled all the time, as if he were coming up for air from the bottom of a pit. He smoked endlessly. I can’t remember, but I think he had emphysema.

He was a very kind and gentle man, warm and friendly by nature. He always asked after me. His children were like that, too. They were very warm towards me, especially Bessie, who paid a lot of attention to me. Often I would walk with my mother to the library and the family story, where Bessie and Sam were employed. When they saw me, it was as if the sun rose, talking to me and offering candy. They were always very good to me.

Visiting Relatives

By Ruth Echenberg Tannenbaum

95 Belvedere Street

Another person who often sat at my grandfather’s table was my uncle Menasseh Echenberg, my grandfather’s brother. He was a tall, elegantlooking man. His wife Eva Holdengraber was a tall craggy woman with a face that looked like Mount Rushmore, carved out of stone. She had kinky blonde hair that had faded to gray. She always wore a house dress with an apron and constantly smoked, with the cigarette dangling from the comer of her mouth as she talked. The rising smoke would make her squint her eyes.

Aunt Eva and Uncle Menassah lived on Belvedere Street, next to where Sherbrooke Pure Milk used to be. A picture of the family taken about 1910 shows a modest brick facade with a group of perhaps 35 or 40 members of our family then living in Sherbrooke (see page 56).

Our house on Prospect Street was ample, with six bedrooms. Nothing was square; it was broad as well as long, with the living room and dining room side by side. There were windows all around admitting natural light.

By contrast, Menasseh’s house was very plain as seen from the front. Inside, it was long, but not broad.

As one entered the front door a central corridor led to the heart of the house, a day room and a huge kitchen. To the right of the corridor was a living room, quite small, which was rarely used. Opposite it was the parlor, whose door was always shut. The day room had couches and divans, tables and straight chairs which provided the family with space and place for naps and visiting. Behind these were the living and dining room, and finally in the back a spacious kitchen.

Proceeding into the kitchen one was aware of a door leading off to the right, into a “summer kitchen”, where meals were prepared during the hot weather – it was a well ventilated terrace surrounded by vines which gave off a greenish coloration, adding to the feeling of coolness.

Returning to the passageway leading to the kitchen one passed two armoires that held dishes, but more importantly, jars of cookies and sweets which were produced in abundance by the fine hand of Aunt Eva, an accomplished pastry chef. She was Rumanian, and had lived in the Near East – many of her recipes were North African. And best of all, she actually made her own Turkish Delight and Rose Water, which she used extensively. This was a source of great awe for me as a little girl.

The kitchen held a huge wood stove as well as a large table and chairs, and it was here that the women of the community used to gather to play poker on Saturday night and sample Eva’s outstanding baking. Aunt Sarah Weinstein, Mindel Niloff, Ethel Smith, Sophie Echenberg, Basel Echenberg, my mother, Rebecca Echenberg and my grandmother, Leah Echenberg, were among the players, all chattering away and consuming the delicious pastries that were being served.

But there was a parallel house – on the other side of the corridor. From the day room there was a door, always kept shut and probably locked, behind which was a richly furnished dining-room, where the fine china, crystal and silverware were kept, and which was opened and used only on “state occasions” – very formal events which I was never to observe. It led back towards the front of the house to a stately salon or parlour furnished in red plush overstuffed sofas and chairs, mahogany sideboards and darkened windows. These rooms were used only for very serious occasions and retained an air of musty mystery.

Eva’s nieces and nephews were all good looking. Her brother Adolf was very handsome. One of her nieces, Edith Holdengraber from Detroit, married Sydney Echenberg in 1936 or 1937. Sydney was good friends with my uncle Leon. This was before Leon met and married Anne Linds. The two of them used to take me and Sydney’s little sister Sarah “ski-joring”. This was an extremely dangerous practice, where they would tie ropes to the back of the car on a cold winter day. We would put on our skis and they would pull us along the snowy streets.

Aunt Eva had other relatives who were to figure in my life – Cousins Beryl and Tullie who were “butchers” on the passenger trains, C.P.R. which ran between Montreal and Halifax, passing through Sherbrooke. Their function was to sell sandwiches and drinks, as well as candy bars and magazines on the train, all the while wearing white jackets and a trainman’s cap. As soon as I was able to travel alone, at about the age of ten, I would visit Montreal for the Christmas holidays or for medical consultations, staying with Aunt Bess Usher or Aunt Bertha Levinson. Often I would be discovered by either Beryl or Tullie who would greet me with loud cries of “How’s Mama? – How’s Papa? – Have a sandwich – Here, take some more!”.

Train trips were sometimes occasions for ingenuity or embarrassment. On one such occasion I was coming home from holidays with the Levinsons. Aunt Bertha had given me 50 cents to buy something in the dining car, so I promptly seated myself and ordered a hot chocolate. Imagine my dismay to find that the bill came to 60 cents – what to do? I spied a large merry gentleman who looked very familiar but whose name I didn’t know. I approached him with a short biography -I’m Ruth Echenberg – Rebecca and

David’s daughter, and I haven’t enough money to pay for my hot chocolate. Could you lend me 10 cents and my mother will pay you back as soon as we get to Sherbrooke. A loud laugh, and a confirmation – “So you’re Ruthie!

Here you are – is this enough?” I retreated to my seat with the right change, and rushed off the train as soon as we got into the station, dragging my mother to the steps where my benefactor was descending. My discomfiture was complete when my mother thanked Senator Charlie Howard for his kindness – for it was the eminent representative to the Senate who had rescued me. It turned out that my mother, as the daughter of Moses Echenberg should be, was a good Liberal, and had worked in Senator Howard’s campaigns when he was a Member of Parliament. Such are the values of political activism -1 learned early!

Visiting the Kitners

My aunt Naomi and Uncle Charles, known to me as Huma and Shama, settled in Megantic, a town at the edge of the wilderness of the Maine woods, where Shama had a watchmaker and jewellery shop, above which they lived with their sons Myer and Murray (known as Mussie). They lived there in the 1920’s and our family would visit from time to time during the summer, driving the over sixty miles on dusty dirt roads, through villages and forests, to arrive in Lake Megantic, a pretty town on the shores of a large lake. The CPR rail line came through the town on its way to St. John’s, New Brunswick and Halifax, Nova Scotia. Here the train was sealed as it headed across the Maine woods that reached up into Quebec. No one was allowed on or off the train until it got to Canadian territory again. Megantic was at the end of the road – nothing but forest out there. Lumbering operations were extensive in the area, and the camps were supplied by seaplanes based on the lake. These were flimsy aircraft on pontoons, and they were tied up at the dock, next door to the Kitners’ store and residence.

Huma and Shama were busy store and home keepers and their two mischievous sons soon became familiar with all the possibilities for adventure. On the occasion of one of our visits, Mussie went missing for several hours. Soon the whole town was looking for him, and they were preparing to drag the lake, when a seaplane landed, and out stepped Mussie with his new friend, the pilot. The outcome was a familiar one, a good thrashing from Shama, who had a very heavy hand.

There were two other Jewish families in Megantic – the Gillmans and the Greenspons, whose daughter Adele was to become the object of perpetual teasing and mischief by the Kitner boys. Whenever I visited we would walk over to the Greenspons, find Adele sitting on the stoop, beautifully dressed and wearing long sausage curls on her head. I might have found something to do with her had my cousins not inhibited me completely. We made her life miserable until she ran in crying, and we went back to the Kitners with a heavily edited account of what we had been playing with Adele.